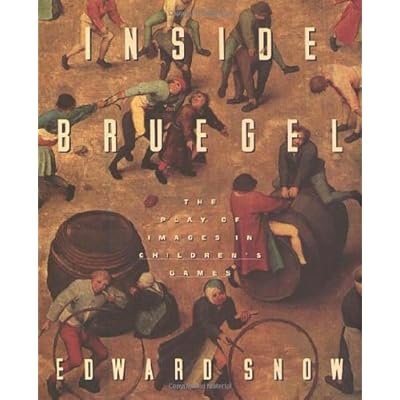

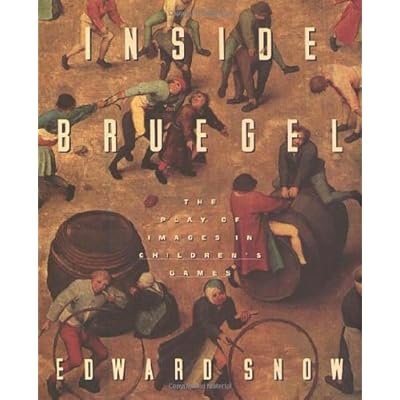

Inside Bruegel: The Play of Images in Children's Games

Category: Books,Arts & Photography,History & Criticism

Inside Bruegel: The Play of Images in Children's Games Details

From Kirkus Reviews Translator and art historian Snow (English/Rice Univ.; A Study of Vermeer, not reviewed) turns a close reading of the multifarious Bruegel into a colorless exercise in pedantry. The Elder Bruegel's range of subjects and richness of detail make it easy to structure a whole book around the imagery of his paintings, a task to which Snow, alas, brings jargon-mongering and donnish analysis. Any art historian would of course be attracted to Bruegel's scope of accomplishment--peasant genres, Bosch-like fantasies, religious histories, parables, landscapes--and his combination of Dutch realism, Renaissance humanism, and medieval motifs. His painting Children's Games, for instance, with its minute social observation, masterful composition, myriad details, and underlying moral subtleties, make it a favorite subject of study. Snow not only examines the significance of almost each frolicking group in the painting, but also contrasts, not always convincingly, the figures with those in other Bruegel canvases. The games Bruegel's children play are not the moralized images of his Netherlandish Proverbs, however, though the two paintings are similarly crammed; nor is the composition of the carefully structured Children's Games as straightforwardly realistic as Peasant Dance. Snow's efforts unfortunately turn into academic interpretations of other academic interpretations or spiral into abstruse theory-speak, featuring ruminations on the ``unstable libidinal field'' of a painting or the ``oasis of pre-volitional well-being'' in a work. Snow may be sensitive to the problem of our aesthetic responses to an artist so subtly nuanced and historically distant, but his impulse is toward amorphous hermeneutics rather than the essence of the images before him. Reading into Bruegel's paintings, Snow renders the Dutch artist, in recondite prose, into an abstract impressionist. ``They were never wrong, the Old Masters,'' as Auden writes, but the same can't be said for this particular commentary on one of those masters. (150 b&w illustrations, one color plate, not seen) -- Copyright ©1997, Kirkus Associates, LP. All rights reserved. Read more Review “Edward Snow has an eye—and a mind—for details. He has lovingly ventured inside Bruegel’s Children’s Games, and his intense, intimate prose enables us to linger in the vast, sprawling scene, savoring each of the marvelous figures and pondering their rich and complex interrelations. This extraordinary sustained act of critical attention will transform our understanding of Bruegel’s art and help to illuminate the meanings of that most elusive and precious human activity, play.”—Stephen Greenblatt Read more About the Author Edward Snow is a professor of English at Rice University. North Point Press has published his translations of Rilke's New Poems (1907), New Poems (1908) [The Other Part], The Book of Images, and Uncollected Poems. He has won both the Academy of American Poets' Harold Morton Landon Translation Award and the PEN Award for Poetry in Translation. Read more Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved. Inside BrugelPART ONEThinking in ImagesAt the ledge of the window in the left foreground of Children's Games (see foldout), two faces are juxtaposed (Fig. 8). One is the round face of a tiny child who gazes wistfully off into space; the other is the mask of a scowling adult, through which an older child looks down on the scene below, perhaps hoping to frighten someone playing beneath him. Bruegel takes pains to emphasize the pairing by repeating it in the two upper windows of the central building (Fig. 9). Out of one of these, another small child dangles a long streamer and gazes at it as a breeze blows it harmlessly toward the pastoral area on the left; out of the other, an older child watches the children below, apparently waiting to drop the basket of heavy-looking objects stretched from his arm on an unfortunate passerby.At the two places in the painting that most closely approximate the elevation from which we ourselves view the scene, Bruegel has positioned images that suggest an argument about childhood. The two faces at the windowsill pose the terms of this argument in several ways at once. Most obviously, they juxtapose antithetical versions of the painting's subject: the child on the right embodies a blissful innocence, while the one on the leftmakes himself into an image of adult ugliness. But they also suggest an ironic relationship between viewer and viewed: we see a misanthropic perspective on childhood side by side with a cherubic instance of what it scowls upon. And at the level of our own engagement with the painting's images, the faces trigger opposite perceptual attitudes: one encourages us to regard appearances as innocent, the other to consider what is hidden beneath them.Interestingly enough, the two faces correspond in all these respects to the opposing interpretations of Children's Games that Bruegel criticism has given us to choose between. The iconographers, looking beneath the games for disguised meanings, view them as the inventions of "serious miniature adults"1 whose activities symbolize the folly of mankind and the "upside-downness" of the world in general.2 The literalists, on the other hand, argue that the games are innocent and carefree, and that they are depicted "without recondite allusion or moral connotation."3 Indeed, the faces at the window can be seen as images of these two ways of looking at things as well as epitomes of the childhood they view. The face on the right presents the ingenuous gaze. It is obviously incapable of perceiving corruption or looking beneath surfaces. Bruegel portrays its innocence fondly but has it gaze off into space, away from the spectacle that he himself has organized. The adult mask, in contrast, peers intently on the scene below, but with a misanthropic scowl that is ingrained in its features, and with eyes that are as empty and incapable of vision as the small child's wistful gaze.The two faces, then, not only suggest that the issues underlying the critical disagreement about Children's Games are thematically present in the painting but also lead one to suspect that neither of the opposing interpretations quite corresponds to Bruegel's own view of things. The mask and the child next to it grow strangely alike, in fact, in their mutual blindness to what the painting gives us to see.4 Bruegel elaborates on what they have in common by opposing both to a girl in a swing behind them. Her active involvement contrasts vividly with their spectatorial detachment.5 Nor can her unrestrained kinetic exuberance be assimilated to the dialectic of innocence and experience they imply. The mask shows childhood growing into ugly, predetermined adult forms, and at the same time pictures the misanthropic, supervisory point of view where such ideas of childhooddevelopment thrive; the face on the right, for all its difference, reciprocates by picturing childhood innocence as fragile and passively vulnerable to corruption. The girl, by contrast, is the image of an empowered innocence: she could aptly illuminate the margins of Blake's "Energy is Eternal Delight."6This cluster of details is paradigmatic of how meaning suggests itself in Children's Games. There is evidence everywhere of a sophisticated dialectical intelligence and a capacity for what Cezanne called "thinking in images" at work binding superficially unrelated incidents into elaborate structures of intent. This is not, however, a version of Bruegel with which we are likely to be familiar. The critical tradition has accustomed us to think of him as a cataloguer of contemporary customs, or as a moralist whose images possess intellectual content only insofar as they illustrate proverbs or ethical commonplaces. Thus the many studies that undertake to identify the games Bruegel has depicted gloss the face on the left as "masking" and the girl in the background as "swinging," but they refrain from mentioning the face on the right, since that child is apparently not playing at anything. The iconographers, on the other hand, concentrate entirely on the mask and make it central to an interpretation that turns the painting into a comment on human folly and "deception."7As different as these approaches are, both address the problem of meaning by removing individual images from the painting's internal syntax and situating them in an external field of reference--in one case the everyday life of sixteenth-century Flanders, in the other a lexicon of conventional significations. Yet the painting's elaborate syntax (if that is not too orderly a term for something so unruly) is the medium in which its thought takes form. Within the apparent randomness of the games there is an incessant linking of antithetical details. We have already seen how the faces juxtaposed at the window are mirrored by two children looking out of the building across the street. The gently floating streamer of one of those children is balanced by the heavy basket of the other. That basket, open and precariously hanging from the boy's arm, is paired with one that is closed and tightly fastened to the wall. This opposition is embodied again in the two boys hanging from the narrow table ledge in front of the building's portico--one clinging to it tightly, the other dangling from it lazily--while behind them a girl balancing a broom on her finger takes up a positionanalogous to that of the girl swinging behind the two children at the windowsill (Fig. 10).Such patterns begin to appear everywhere as one becomes attuned to the way the painting "thinks" in terms of oppositions. And where its pairs seem most obviously to generate significance, they tend to frame questions about the place and nature of human experience, not settled moral judgments about it. An especially pointed example of how the difference-creating syntax of the painting counteracts the impulse to burden individual images with moral content can be seen in the two barrel riders in the right foreground (Fig. 11). Taken by themselves they would be quite at home in any late-sixteenth- or early-seventeenth-century emblem book, where they would no doubt signify the treachery of worldly existence. But Bruegel has paired their mount with another barrel and established an elaborately antithetical relationship between them: one upright, the other tipped over on its side; one contended with by two awkwardly cooperating boys, the other being called into by a curious girl. Seen in terms of this opposition, the two boys seem an emblem not so much of the folly of the world as a certain mode of relating to it. They and the girl present us with dialectically related ways of worldmaking.8 One takes the object in hand in order to dominate it and undoes a given stability in order to create a man-made equilibrium; the other "lets be" and calls forth (into) the object-world's mysterious resonance. The painting works many subtle variations on this distinction, and they will be discussed later in this study. But what needs to be stressed at the outset is the presence in Children's Games of a shaping intelligence that tends to subsume moral issues in dialectical questions about human beings' place in a world that can scarcely be conceived apart from their bodily and imaginative participation in it.There is also opposition within individual images. Time and again a detail will cause the viewer to vacillate between innocent and darkly emblematic readings. We know, for instance, that the boy running up the incline of a cellar door in the receding part of the street is only playing a game, and we can feel the fun of it; yet it is difficult to resist the adult perception that turns him into a figure of futility and despair. The children in the foreground play innocently at rolling hoops, but a sophisticated viewer must strain not to respond to them as evocations of human emptiness.9 A youngster in a cowl whipping a top under a Gothic arch (Fig. 12) can with the blink of an eye suddenly evoke the scriptural Flagellation or the judicial whipping post. A boy on stilts and an open-armed girl beneath him (Fig. 13) can conjure the iconography of the Crucifixion. Are such ambiguities and foreshadowings "in" the games or "in" our perception of them? Does the mask with the grimace on it represent the terrible adult countenance into which the children are already in the process of growing or the distorted perspective through which adults observe them? Is play a rehearsal for adulthood or is adulthood a loss of the spirit of play?Such questions have no simple answers, especially in the form that Children's Games poses them. They are a function of instabilities within the perception of childhood (and childhood play) that Bruegel deliberately exploits. We will be concerned throughout this study with the fields (thematic, cognitive, kinetic, cultural, iconographic) within which these instabilities operate, and with the various ways they infiltrate the act of viewing. But again, it is worth noting at the start how often emblematic and iconographic cues that at first glance might appear to fix the painting's meaning turn out to be only one facet of an unstable, overdetermined perception; and how, as a result, "references" to external conventions and contexts tend to get subsumed in cognitive uncertainty and an unanchored connotative play.Copyright © 1997 by Edward Snow Read more

Reviews

I purchased this book as a research tool for an art appreciation enrichment volunteer project I do at local elementary schools. The students just love spotting all the activities in Bruegel's amazing painting in which the children are engaged and this book really helps me highlight and discuss each one. The pictures and illustrations are great and very detailed. There also is extensive analysis of the deeper and allegorical meanings of the painting which was intellectually interesting to me but not the purpose for which I use the book. I would recommend this book to anyone who really wants to "get to know" this painting!